Danger Zone: Photographing the Kilauea Volcano

Here's a tip: If you find yourself photographing in the area of an erupting volcano and your feet are getting hot, it's a sure sign you should not be standing where you're standing.

We got that from Mike Mezeul, who photographed the Kilauea volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii in late May and mid-June, 2018, on two trips covering 14 days.

Of course it's extremely unlikely you'll get a chance to do anything like that, and quite rightly so—it's dangerous. Even though Mike is an experienced photographer of severe weather and natural disasters, and was an accredited photojournalist on assignment in Hawaii, he, like other members of the media, was allowed into the area only when escorted by the National Guard.

And still...

"I was pretty scared," Mike says. "I'd been there [photographing Kilauea] in 2016, but this was very different. We needed to have masks and helmets, stuff's falling out of the sky, cracks are opening, things are blowing up. All my feelings of experience and confidence from my first time in 2016 went out the window as soon as I arrived this time. We were told the first day that 'no human being should be going where you're going, and even though you're with the military, that does not guarantee we will come in to rescue you if you need it.'

"It was pretty serious stuff, and the people on patrol were not to be fooled with."

Vantage Points

Mike's credentials gave him supervised ground access; air and sea coverage were his doing with helicopter and boat charters. "You're allowed to make your own arrangements with rental or charter operations for helicopters and boats," he says, "but those companies are on strict regulations as well. For helicopters there are TFRs—temporary flight restrictions—over the disaster area, so even though we could enter the area, we could not be below 3,000 feet because for any sort of evacuation or emergency, military or medical helicopters would be flying at lower altitudes and all other helicopters need to be out of their way. Also, there are areas where residents still live, and they don't want to hear a dozen helicopters an hour going over their houses."

And then there's the really scary part. "It's the gases up there in the air that you can't see. There's an abundant amount of sulfur dioxide in the air, and that can be lethal. The higher up you are, the less chance of running into it, and we still ran into it a couple of times. The pilots for the company I flew with were outstanding, and very knowledgeable on reading the wind, so they can see which way the gases will be flowing and they stay upwind as much as possible."

There's danger from the gases on the ground as well, and at least one time the media and the National Guard had to quickly evacuate an area. "They monitor the gases and the lava flows, and they always made sure we had two evacuation routes."

The media were responsible for bringing their own respirators and masks. "The National Guard will not take you out if you don't have the gear. We were required to have breathing equipment and eye protection, and we had to wear hardhats."

The green oasis amid hardened lava was most likely a hill, around which the lava took a lower path. "I shot this and a couple of days later flew over and the hill no longer existed; it was overtaken by the lava. That little dirt road going through the frame made me wonder, Where did that road lead? Maybe to a beautiful beach? Now everything is gone." Mike had no stabilizer for his helicopter shots—just fast shutter speeds and VR activated on all the lenses that had it. D850, AF-S NIKKOR 200-500mm f/5.6E ED VR, 1/2500 second, f/5.6, ISO 2500, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

Lava erupting from a fissure on what was a residential street reached 280 feet as Mike photographed it. "There are homes underneath that," he says. "This was the most powerful moment for me—I could feel the heat roaring out of the fissure and it sounded like a jet engine at takeoff." This fissure was putting out 28,000 gallons of lava per second, but now the cinder cone it built up—you can see it at the bottom—has risen higher than the flow. D850, AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8G ED VR II, 1/1000 second, f/9, ISO 1600, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

Mike took this shot of the fissure in the previous photograph as he was about to drive away. "All that vegetation should be green—it's dead from the sulfur dioxide." D850, AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8G ED, 1/320 second, f/9, ISO 1600, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

The truth is that to do this photography, you have to constantly keep in mind all the things that can harm you, or worse.

"I was terrified, I'm not going to lie to you," Mike says. "I debated up until the night before booking my flight if I was going to go because I knew what I'd be dealing with: burning homes, methane explosions, cracks in the ground as deep as 30 feet and lava flowing very quickly—and not small amounts of it. The fissure that's currently erupting is putting out 28,000 gallons of lava per second. There were a couple of times we had to evacuate very quickly because lava broke through a barrier. I remember being rushed into the back of a pickup truck and doing 70 miles an hour down residential roads trying to get to safety."

An isolated area, higher than the rest, surrounded by cooled lava. "I talked with a lot of the local residents," Mike says, "and many were optimistic and in good spirits. They believe that Pele [goddess of fire, lightning, wind and volcanoes, known as "she who shapes the sacred land"] is in control, so whatever is happening is out of their control, and they can only witness her working. So when I shot images in a fine art style, I felt a little bit better hearing that locals considered this part of Hawaii, part of nature." D850, AF-S VR Zoom-NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G IF-ED, 1/800 second, f/5, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

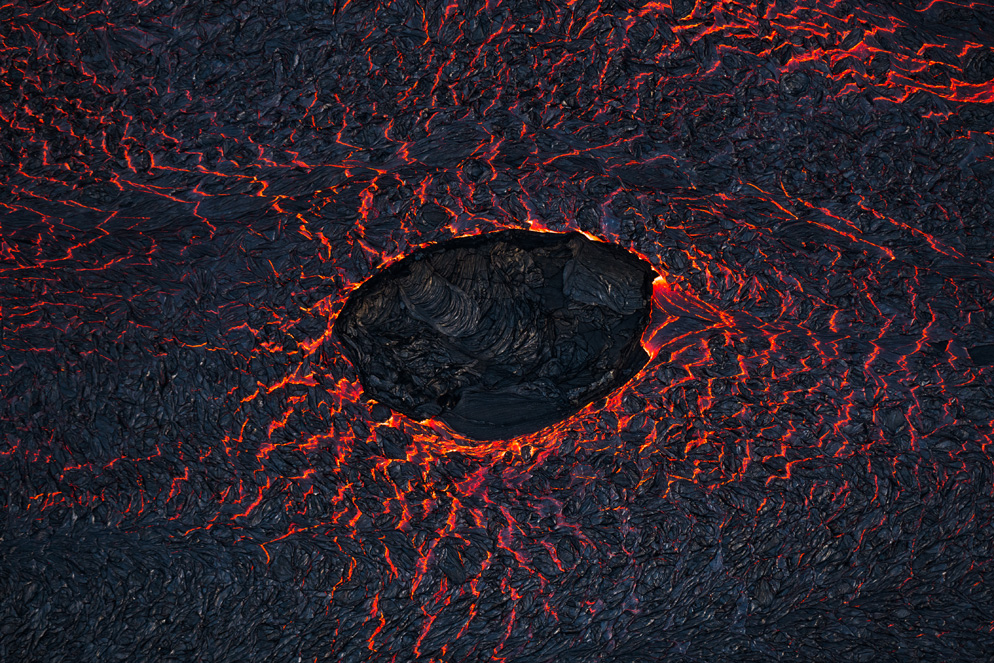

"In some places the river of lava is 1,000 feet wide, and an island in the middle is called a 'lava boat'—a piece of the eruption that's broken off; it's cooled lava that's now floating down the river of lava." Mike estimates the piece was 30 to 40 feet in diameter. When he posted this photo on Facebook, he called it Pele's Eye. D850, AF-S VR Zoom-NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G IF-ED, 1/640 second, f/5, ISO 320, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

For the Record

So...why? Why do it, why risk it? And what is the National Guard doing keeping an eye on photographers?

Last question first: "To keep us safe is the main thing," Mike says, but also to insure that this catastrophic event is documented. "The mayor of Hawaii wanted the press there, he wanted people to have the news, to see what was going on. The scale of the event, how intense and dangerous it is, is unbelievable. I heard that according to USGS—the United States Geological Survey—this was the hottest lava they've ever recorded, and for this to take place in a residential area is overwhelming."

The National Guard officers charged with guiding and protecting the media were not ordered to do it; they volunteered for the duty.

"None of the opportunities, and none of the images, would have been possible without them," Mike says. "They knew exactly where to take us—where the stories were, where the shots were—and how to get us out. They were monitoring the sulfur dioxide levels and the hazards where we shot. Without those three guys—and I want to name them: Major Hickman and Sergeants Jackson and Ching—we wouldn't have been able to do what we did."

Mike's reasons for being there were complex. "The science part of me, the nerdy part of me, really loves seeing nature at work," he says, "but there's an important human aspect, too: to see what these people are going through, and hoping some of the images I've shot and I've been sharing will bring some awareness that, hey, these people need help; they've lost everything. This area is a low-income area of Hawaii; they live near a volcano, but people can be taken out by a tornado, a flood, a hurricane, an earthquake—so many people live near what can quickly be a natural disaster. There's risk everywhere.

"So here I wanted to show not only the power of nature but also take photographs that tell the story of human loss."

A lot of the other photographers were photographing the fissure above the trees, but Mike thought the playground, where kids and families came, which was now covered with tephra, the rock fragments from the volcano, was the story. "I needed to shoot this because it tells the story of what once was; it's the human element." D850, AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8G ED, 4 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1250, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

"I'd done two boat rides because I wanted to catch one of these. They're are called littoral explosions—they happen when lava enters the water from the ocean floor, rockets up and explodes when it reaches the surface. They sound like depth charges below, then immediately you'll see a massive explosion chucking basketball and bigger-size pieces of lava into the air. They can reach up 100 to 200 feet. You can see pieces of red hot lava in the shot. We had seven or eight of these happen—it was terrifying. It's nature; you can't control it." D850, AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8G ED VR II, 1/1000 second, f/4.5, ISO 500, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

Geared Up

"I chose to go heavy," Mike says. "If I was going to do this, I wanted to have whatever I needed to get it right, in any situation. I brought everything with me every day because I didn't know if a shot was going to be there the next day—everything changed so rapidly, sometimes hour to hour. One day I took a photo of an eruption going 200 to 300 feet in the air—that shot can't be made anymore because a cinder cone has built up that's higher than the eruption."

So, he says, "you drag it all along—you don't want to miss a thing. You cover it all, cover as much as possible, and cover it from land, sea and air."

To do that he carried a D850 and a D810, a tripod for long exposures and a number of lenses from the 14-24mm to the 200-500mm. "I knew each circumstance was going to be different and situational. The first day we were able to get a hundred feet away from an erupting fissure, and in that case I'm shooting 24-70mm or 70-200mm. Then there were images I took of people with the 14-24mm—one was of two guys standing in the middle of the road wearing gas masks and there's a fissure erupting next to them. When I was up in a helicopter, I wanted the extra reach of the 200-500mm."

None of his gear could overcome the problem of rising heat waves distorting and blurring images. When a fissure created a lava river, whether large or small, and that river was between Mike and the fissure, he'd get distortion from the resulting heat waves. In places where the waves were really bad, he had to accept that the images were going to look soft, but there were places where moving 40 feet left or right got him around the problem. "[In] some of the areas I shot from, the huge lava channel was flowing towards me, so the heat waves were a big issue. Other areas, I was on the other side of the channel and had a beautiful clean shot." And in images of the lava rivers shot from a helicopter, heat waves weren't a factor at all.

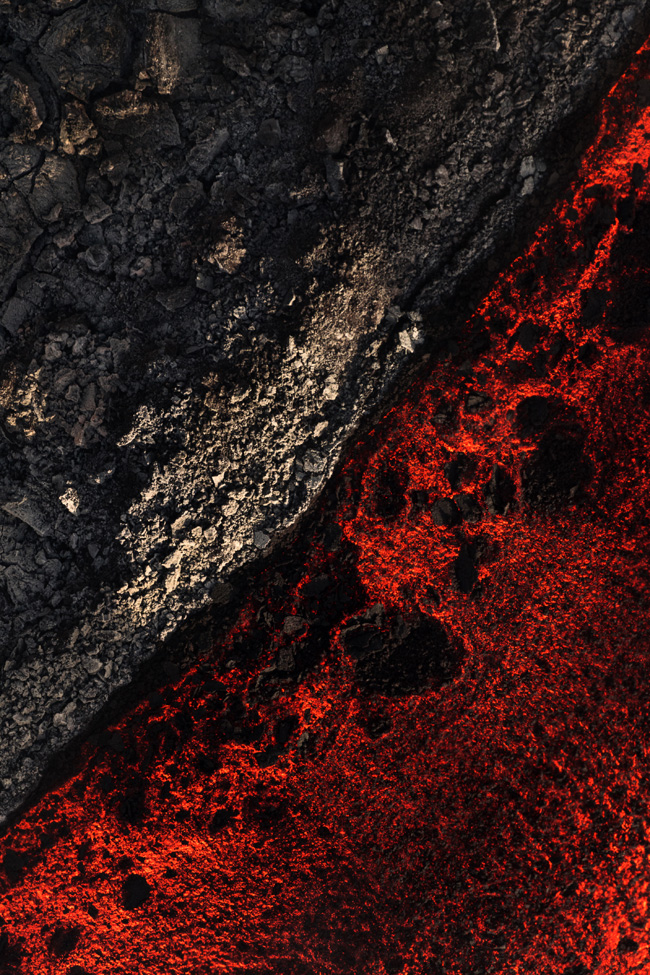

The lava river flows next to cooled lava in one of Mike's fine art images. D850, AF-S VR Zoom-NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G IF-ED, 1/1250 second, f/4, ISO 250, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

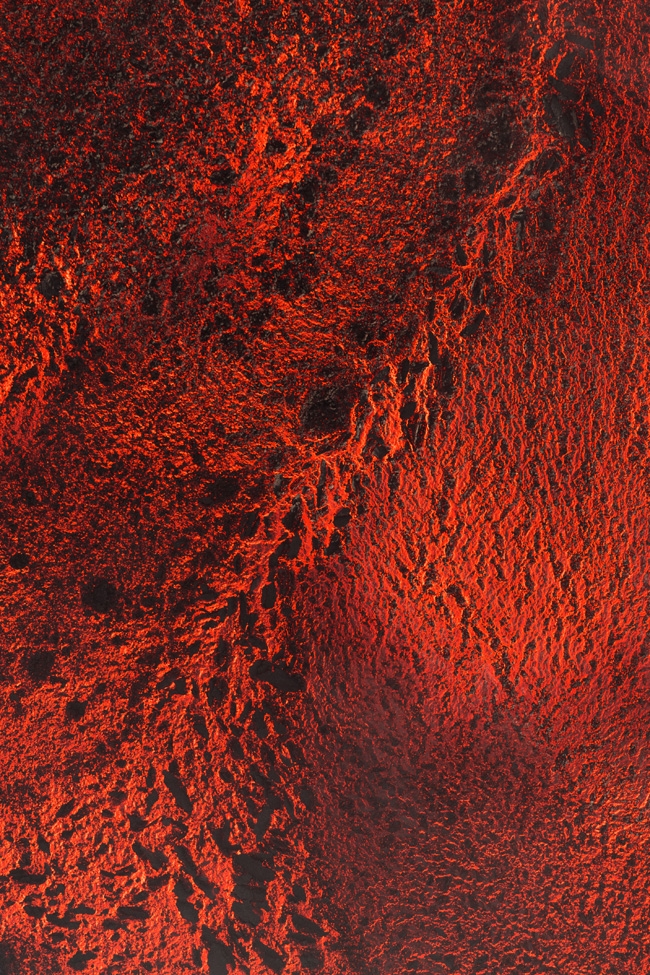

What caught Mike's attention was the different ways the river of lava was glowing with reflected sunlight, and the details of the black chunks of cooling lava—"some of them the size of school buses." Mike says the difference in textures is due to how fast a section is moving, cooling and crusting, and also the topography beneath the section. "The area on the right side of the image was moving faster than the left." D850, AF-S VR Zoom-NIKKOR 200-400mm f/4G IF-ED, 1/1250 second, f/4, ISO 250, manual exposure, Matrix metering.

The Balance

There's no overstating—in case we have to emphasize it one more time—how hazardous this photography was, and we wondered how Mike was able to balance his concentration on making pictures with his awareness of constant dangers amid quick-changing situations.

"It's 50-50 as far as what I called the split between thinking about photography and thinking, I've got to stay alive," he says. "The National Guard officers watched our backs, but we still had to be aware of where we were stepping and what was going on. The first thing I did when I walked to a scene was analyze the hazards. Then I'd make sure of where it was good to stand and not good to stand. I'd take my shots and then immediately reanalyze the situation—that was something the Guard told us to do: always be reanalyzing. Things changed so quickly that 30 seconds later there'd be lava where there wasn't lava, and when you're doing this kind of photography, you can't afford to be taken by surprise."

Make an Appointment

D810 and an AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED, at 25 seconds, f/2.8 and ISO 2500, with the camera set for manual exposure and Matrix metering.

Mike Mezeul took this photo in 2016 when the Kilauea volcano was active, but not to the extent of its 2018 eruption. Most people who saw it posted on the internet thought it was faked.

It's not.

"Everyone lost their minds over his one," Mike says. "Cooling lava, the moon, the Milky Way, Mars and Venus, an iridium flare and the glow of lava entering the ocean—all in one shot, which everyone said was impossible."

But whatever it was—luck, providence, right place at the right time ("about ten p.m." Mike remembers)—it was certainly not impossible. It was all happening at the instant he took the image.

Let's break it down:

The lava, the moon and the Milky Way need no explanation. The iridium flare to the left of the Milky Way, on the other hand, might: it's a satellite flare that occurs when antennas of an iridium satellite catch and reflect sunlight. Iridium is a silvery-white metal—perfect for its catch-and-reflect role in this photo.

Mars and Venus are visible to the right of the Milky Way on a rough horizontal line at about the nine and (almost) three o'clock positions.

Mike made the shot, with a D810 and an AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED, at 25 seconds, f/2.8 and ISO 2500, with the camera set for manual exposure and Matrix metering.