Two Photographers Plus 50 NIKKOR Lenses and Four Z 7 Cameras Equal a Breathtaking Time-Lapse Video

Earth, Wind & Inspire - Stunning 8K Time-Lapse video created using the Z 7 full-frame mirrorless camera and 50 different NIKKOR lenses.

Here's the elevator pitch for the idea: Wouldn't it be cool to make time-lapse videos at particularly photogenic places in particularly photogenic situations with Z 7 cameras and...oh, let's say, 50 different NIKKOR lenses of various vintages—and then combine selected scenes into a seamless, ultra-high definition 8K video.

Well, sure. And we're doing this because....?

Because we can. We have a vast array of NIKKORs past and present in a vast array of focal lengths and zoom ranges, and we'd like to demonstrate their capability, quality and consistency in a pretty imaginative way.

The project was green lit, and the adventure began.

Photo Duo

Mark Kettenhofen, a tech rep for Nikon Professional Services in the US, spent the most time on the project—seven months. Chris Ogonek, product and training specialist for Nikon Canada, spent about three weeks, but traveled more miles. Both photographers began—Mark in the States, Chris in Canada—by listing locations and getting permits and permissions to photograph.

Mark was the hike, camp and explore photographer; Chris, the fly in, rent a car, stay in a hotel, photograph and move on shooter. "Mark had a different plan than I did," Chris says. "He was out to create the best time lapse he could from a few amazing locations, whereas I wanted to show different areas of Canada—the Canadian Rockies, Niagara Falls, Banff National Park, areas of Toronto, Ottawa, Vancouver—places thousands of miles apart. So I covered more territory, but he was able to more closely focus his goals and go hardcore at a few locations."

Critical Factors

The project took place in the early days of the Z 7, and neither photographer had much experience with the camera. But it was a Nikon, and so the learning curve wasn't much of a curve at all and the performance of the system, the adapter and the lenses was seamless.

And in one instance, even better than seamless. Chris used a tilt/shift perspective control lens—a PC-E Micro NIKKOR 85mm f/2.8D—on the Z 7 for the sequence of folks moving across the river bridge, and the combination of tilt/shift lens and mirrorless camera made for quicker, smoother and more confident shooting as the camera's electronic viewfinder and Focus Peaking allowed him to see the results of the movements of the lens and verify focus before he shot the sequence. "The Z 7 made using the PC lens a breeze," Chris says.

After seamless performance, the most important factor for the project was the standard set by the photographers for the time-lapse sequences. "This was the key," Mark says. "In every instance, I shot at least 300 images, which gave me, at a frame rate of 30 frames per second, at least ten seconds of video to work with in post production." Chris shot to the same standard.

"It was a critical decision," Mark adds. "To make the series of time-lapse images look as smooth as possible from frame to frame over the 300 frames, almost everything I shot was at a half-second interval, regardless of the speed of the movement—whether water or clouds or a sunset. The half-second created minimal movement from frame to frame, so in post production I could either speed up or slow down that [video] file for that specific sequence if I needed to preserve smoothness."

Post production was necessary. The Z 7 will produce 4K time-lapse video in-camera—no computer needed—but for 8K, post-processing assembly of the individual sequences is required. Software for this process, and for editing of the sequences, is widely available. Mark, who did all the post-processing work, used Adobe After Effects.

All time-lapse sequences are manually set. There's nothing automatic—you can't have changes that could create differences in color tone or contrast or exposure.

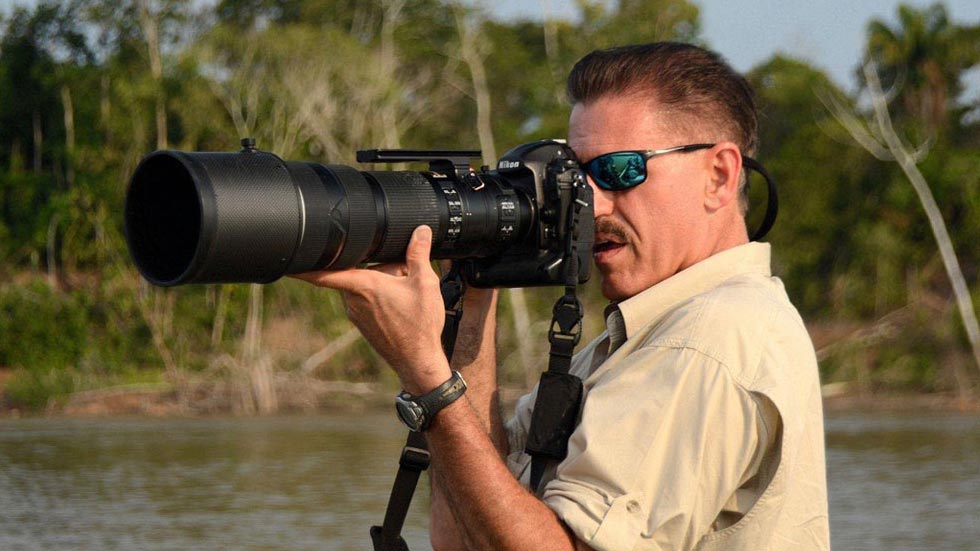

Photo by Mark Kettenhofen.

Photo by Mark Kettenhofen.

The Gear

The NIKKOR lenses were a mix of the photographers' personal glass and Nikon inventory, and spanned years of manufacture. As far as Mark knows, the oldest lens he used was a 55mm Micro-Nikkor circa 1979, and Chris counts an AF 20mm lens from the early 1980s as the oldest he used. The most recent glass was used by Mark—the NIKKOR Z 14-30mm f/4 S. Chris shot with 18 lenses, Mark with 40.

Each photographer had two Z 7 bodies, and Mark added a slider—essentially a portable, motorized dolly and a 12-volt battery to power it to his equipment for the project. "You have to time the slide—the movement of the camera—with the camera's built-in intervalometer, and it takes some calculations and practice to make sure the slide doesn't come to an end before the series of images are shot."

It was worth the effort. A time-lapse sequence depends on movement—it could be light, water, clouds, the sun or moon, but something has to move, and Mark knew there'd be places where motion wasn't going to happen on its own. "If there's already movement at a location, it's probably not going to be a slider shot," he says, "but in Olympic National Park there's the Hoh Rain Forest, and I went to one section because of the ferns at that location—they grow to epic proportions, four or five feet high and just as wide. But the ferns don't move, and the forest is so thick and dense you can't see the clouds, so movement had to be created. The shot I envisioned was to have to the camera looking as though it were flying through the ferns to reveal the forest." And for that, he needed the slider.

Plans of Action

The time-lapse sequences for a project of this scope involved so many elements that the photographers had to have detailed plans—a methodology," Mark says, "beyond the taking of pictures. You have to consider the location: is there visible movement? And the weather: it doesn't have to be nice—adverse weather creates the most dynamic images, but it has to be consistent."

Most of the places Mark chose were well-known to him; a few—like Mount Rainier National Park—were on his bucket list. "I tried to mix in iconic places, like Reflection Lake in Rainier, sometimes to cue other photographers. Other places, like Bears Ears National Monument, are extremely remote and few people go there. I hiked over 23 miles in a period of two-and-a-half days at Bears Ears, carrying everything—tent, sleeping bag, food, water, gear. And some places I'd seen only in pictures—like Bandon Beach in Oregon, with its Wizard's Hat natural formation."

There's also a methodology for the camera settings. As you might expect, automatic settings aren't ideal for time-lapse. A change in the scene will trigger a change in aperture or shutter speed, white balance or focus, and those changes will cause flickers in the image. "All time-lapse sequences are manually set," Mark says. "There's nothing automatic—you can't have changes that could create differences in color tone or contrast or exposure." Because manual focus is necessary, depth of field is key, so whenever possible f/22 was his aperture choice.

Figuring out f/stop and shutter speed settings required studying the location and the scene, often visiting two or three times to take readings over a period of consistent weather. In a valley in Olympic National Park, Mark saw the beautiful effect of light moving through the scene. "Fingers of sunlight danced down across the moss," he says. "I sat for two hours watching the light move and I thought, This is the sequence I need. Next day I came back, set the camera up and when the light hit the moss I walked over and metered on that light. That gave me a base exposure to manually set the camera. Then I did a test series. It looked good, and the next day I came back and made the sequence you see in the video. People may look at that shot or others like it and say, 'Man, you were really lucky,' but it's not luck at all. It takes an amazing amount of pre-planning and what I call 'photographic precognization.' You have to understand what the light is going to do at a particular location at a particular time to capture moments like that."

So after all these years, all the incredible technology, all the magic today's cameras and lenses deliver—it comes back around to awareness of a basic starting point of photography: what is the light going to do?

The Key Word

We mentioned it at the beginning, it was always on the minds of the photographers and it's evident in the viewing of the video: consistency.

Consistency In the frame rate and the intervals and the settings and the weather. And in the reliable consistency of the NIKKOR lenses. Over the years, the camera models and types, from film to digital to mirrorless, chances are if you shot with it then, you can shoot with it now and get the same quality results. Over multiple generations, NIKKORs have delivered quality, reliability and consistency.

You've viewed Earth, Wind & Inspire, and we think it's likely that if the lens identifications weren't featured, you wouldn't be able to tell whether a sequence was photographed with a lens made 40 years ago or one made literally within months of its use on the project.

We think that's pretty cool, too.

By the Numbers $

Mark Kettenhofen's Excellent Time-Lapse Adventure

-

Seven months shooting.

-

5,675 miles driven.

-

385 miles hiked.

-

Highest temperature on location: 98° F.

-

Lowest temperature on location: -14° F.

-

12 nights in a hotel.

-

45+ nights camping.

-

57,300 images recorded.

-

Three black bear sightings.

-

Two lost lens caps.

-

One pair of hiking boots worn out.

-

One pair of hiking boots stolen from outside tent.

-

One question: "When can I do it again?"